Chapter3 - Counting 101 - Sums

Book - Python Algorithms by Magnus Lie Hetland

Chapter 3 - Counting 101

About

The concept of sums and some basic ways of manipulating them.

Two major sections: Two fundamental sums and recurrence relations.

And, there are little sections on subsets, combinations, and permutations.

Sums

The greatest shortcoming of the human race is our inability to understand the exponential function. — Dr. Albert A. Bartlett, World Population Balance Board of Advisors

In python,

x*sum(S) == sum(x*y for y in S)

In mathematical notaion,

\[x\sum_{y\in S}y = \sum_{y\in S}xy \]

Supplying limits to the sum

“sum f(i) for i = m to n” is written as

\[\sum_{i=m}^{n}f(i)\]

s = 0

for i in range(m,n+1):

s += f(i)

Manipulation Rules

\[c\sum_{i=m}^{n}f(i) = \sum_{i=m}^{n}c\cdot f(i) \]

Distributivity(분배법칙) & Associativity(결합법칙)

c(f (m) + … + f (n)) = cf (m) + … + cf (n).

\[\sum_{i=m}^{n}f(i) + \sum_{i=m}^{n}g(i) = \sum_{i=m}^{n}(f(i)+g(i))\]

sum(f(i) for i in S) + sum(g(i) for i in S)

# Equal

sum(f(i)+g(i) for i in S)

Two sums, or Combinatorial problems

Presenting them as two forms of tournaments.

The round-robin tournament(리그전) and the knockout tournament.

Especially, consider a single round-robin tournament.

In a single round-robin tournament,

Q) How many matches or fixtures do we need, n knights competing?

In a knockout tournament,

the competitors are arranged in pairs, and only the winner from each pair goes on to the next round.

Q) For n competitors, how many rounds do we need, and how many matches will there be, in total?

Shaking Hands

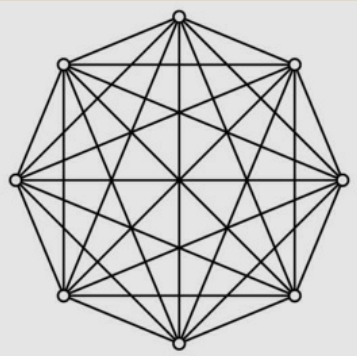

The round-robin tournament is equivalent to shake hands with all the participants, or equivalently how many edges are there in a complete graph with n nodes.

Complete Graph

“all against all” situation

make it all against all the other, yielding (n-1).

Getting n(n-1)/2, which is \(\theta(n^2)\)

The other way of counting: The first one competes with n-1 others. Among the remaining, the second one competes with n-2. This continues down to the next to last, who competes the last match, against the last one (who competes zero matches against the zero remaining one.)

This gives us the sum n-1 + n-2 + … + 1 + 0, or sum(i for i in range(n))

\[ \sum_{i=0}^{n-1}i = \frac{n(n-1)}{2} \]

Arithmetic Series(등차수열)

A sum where the difference between any two consecutive numbers is a constant \(d\).

Assuming this constant is positive, the sum will always be quadratic. In fact, the sum of \(i^{k}\) , where i = 1. . . n, for some positive constant k, will always be \(\theta(n^{k+1})\). The handshake sum is just a special case.

The Hare and the Tortoise (토끼와 거북이)

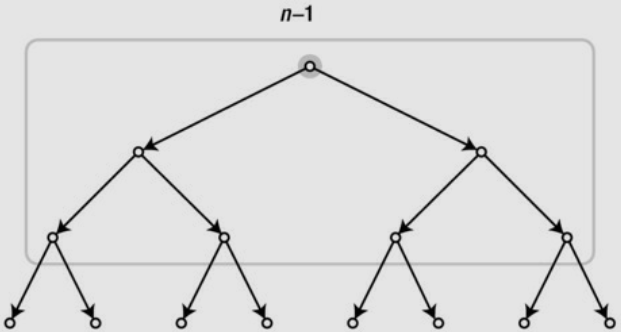

In knockout system, want to know how many matches they’ll need.

The solution can be a tricky to find, or blindingly obvious.

Tricky one

First round: all the competitors are paired, so we have n/2 matches.

Second round: half of them, so we have n/4 matches.

Keep halving until the last match, giving us the sum n/2 + n/4 + n/8 + … + 1, or, equivalently, 1 + 2 + 4 + … + n/2.

Obvious one

In each match, one knight is knocked out. All except the winner are knocked out (and they’re knocked out only once), so we need n–1 matches to leave only one man (or woman) standing.

\[ \sum_{i=0}^{h-1}2^{i} = n-1 \]

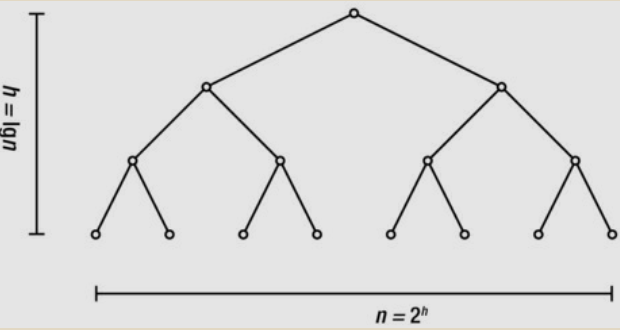

The upper limit, h-1, is the number of rounds, or h the height of the binary tree, so \(2^{h} = n\).

The hare and the tortoise are meant to represent the width and height of the tree, respectively.

One grows very slowly, while the other grows extremely fast.

\[ n = 2^{h} \]

\[ h = log_{2}n \]

Logarithm and Exponential

Up down game

pick the right number in range of \(10^{90}\)

from random import randrange

n = 10**90

p = randrange(10**90)

>>> p == 52561927548332435090282755894003484804019842420331

False

Best strategy to pick the number is halving the number of remaining options.

you can actually find the answer in just under 300 questions.

from math import log

n = 10**90

print(log(n, 2)) # base-two logarithm

# 298.9735285398626

This is why logarithmic algorithms are so super-sweet.

From one, double it 64 times repeatedly.

Started at \(2^{0} = 1\), the total would be \(2^{64}-1\)

Exponential growth can be scary.

Related to recurrence

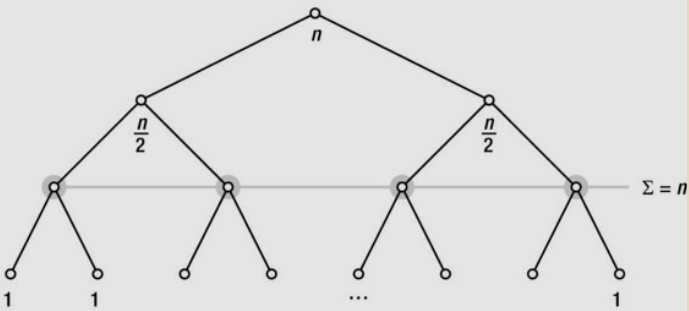

The tree represents the doubling from 1 (the root node) to n (the n leaves), representing the halvings from n to 1. When working with recurrences, these magnitudes will represent portions of the problem instance, and the related amount of work performed, for a set of recursive calls.

When we try to figure out the total amount of work, we’ll be using both the height of the tree and the amount of work performed at each level. We can see these values as a fixed number of tokens being passed down the tree.

As the number of nodes doubles, the number of tokens per node is halved; the number of tokens per level remains n.

Geometric Series (기하급수)

A geometric (or exponential ) series is a sum of ki, where i = 0…n, for some constant k. If k is greater than 1, the sum will always be \(\theta(k^{n+1})\). The doubling sum is just a special case.

Subsets, Permutations, Combinations (부분집합, 순열, 조합)

The number of binary strings of length k should be easy to compute. The string length, k, will be the height of the tree, and the number of possible strings will equal the number of leaves, \(2^{k}\).

The relation to subsets is quite direct: If each bit represents the presence or absence of an object from a size-k set, each bit string represents one of the 2 k possible subsets. Perhaps the most important consequence of this is that any algorithm that needs to check every subset of the input objects necessarily has an exponential running time complexity.

Permutations are orderings. If n people queue up for movie tickets, how many possible lines can we get? The number of permutations of n items is the factorial of n, or n!.

\(_{n}P_{r}\)

Combinations are a close relative of both permutations and subsets. A combination of k elements, drawn from a set of n, is sometimes written C(n, k), or, for those of a mathematical bent: \(\begin{pmatrix}n\\k\end{pmatrix}\)

This is also called the binomial coefficient (or sometimes the choose function) and is read “n choose k.” While the intuition behind the factorial formula is rather straightforward, how to compute the binomial coefficient isn’t quite as obvious.

\(_{n}C_{r}\)

In fact, we could allow these friends to stand in any of their k! possible permutations, and the remainder of the line could stand in any of their (n–k)! possible permutations without affecting who’s getting in.

\(\begin{pmatrix}n\\k\end{pmatrix} = \frac{n!}{k!(n-k)!}\)

This formula just counts all possible permutations of the line (n!) and divides by the number of times we count each “winning subset,” as explained.

nk. The fact that C(n, k) counts the number of possible subsets of size k and 2 n counts the number of possible subsets in total gives us the following beautiful equation:

\(\sum_{k=0}^{n}\begin{pmatrix}n\\k\end{pmatrix} = 2^{n}\)

Pseudo-Polinomiality: Primality Test and Knapsack Problem

It’s the name for certain algorithms with exponential running time that “look like” they have polynomial running times and that may even act like it in practice. The issue is that we can describe the running time as a function of many things, but we reserve the label “polynomial” for algorithms whose running time is a polynomial in the size of the input—the amount of storage required for a given instance, in some reasonable encoding.

Primality Check

This problem has a polynomial solution, but it’s not.

def is_prime(n):

for i in range(2, n):

if n % i == 0:

return False

return True

This might seem like a polynomial algorithm, and indeed its running time is \(\theta(n)\).

The problem is that \(n\) is not a legitimate problem size.

The size of a problem instance consisting of \(n\) is not \(n\), but rather the number of bits needed to encode \(n\), which, if \(n\) is power of 2, is roughly \(\log(n+1)\).

For an arbitrary positive integer, it’s actually floor(log(n,2))+1.

Let’s call this problem size (the number of bits) k. We then have roughly n = 2 k–1. Our precious \(\theta(n)\) running time, when rewritten as a function of the actual problem size, becomes \(\theta (2^{k})\), which is clearly exponential.5 There are other algorithms like this, whose running times are polynomial only when interpreted as a function of a numeric value in the input.

Knapsack problem is pseudo-polynomial.

Looks, \(O(n*m)\): n is the number of items, m is the max weight.

But, to solve this problem, you have to build a table. And this table requires cross referencing. And the amount of space that the table stores relys on the number of items(input) and maximum weight. The space that the table takes is going to take is greater than polynomial time. It grows exponentially.

Difference between Big Oh, Big Omega and Big Theta

- Big Oh notation (O) :

Big oh notation is used to describe asymptotic upper bound. - Big Omega notation (Ω) :

Just like O notation provide an asymptotic upper bound, Ω notation provides asymptotic lower bound. - Big Theta notation (Θ) : Upper bound and Lower bound.

Complexity https://www.geeksforgeeks.org/difference-between-big-oh-big-omega-and-big-theta/

knapsack problem is pseudo-polynomial. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qFeBDh-SoaA

knapsack problem: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xCbYmUPvc2Q

Leave a comment